The NY Times Company third quarter financial report for 2013 suggests a mixed result from the rise of their digital paywall operations.

First, the good news - overall revenues are up, fed by circulation increases. Third quarter subscription revenues from all digital sources (paywalls, apps, etc.) were up 29% from a year ago, although digital circulation revenues contribute just slightly more than 10% of total revenues.

The not so good news comes from looking a bit deeper. Despite adding $10 million in digital paywall revenues, total revenues were up only $6 million. The press release did not break out print circulation revenues separately, yet the overall numbers suggest that the increased prices for print subscriptions imposed earlier this year aren't enough to fully compensate for continuing declines in print circulation. The continued decline in print readership is also reflected in the 1.6% decline in print advertising. What is surprising is that digital advertising revenues at the Times also fell - and at a faster rate (3.4%) despite digital circulation increases. The release tries to attribute this to "secular trends" - but digital advertising revenues (overall) showed 18% gains in the first half of this year. Granted, the fastest gains were in areas other than traditional display ads. A more credible analysis is that the Times is not getting its share of a growing online advertising market, most likely because it's not pursuing more lucrative online advertising options (and the paywall does make some of those difficult, if not impossible, to implement), and the overall readership loses resulting from the paywall restrictions.

In the short term, the NY Times is maintaining revenues growth through expanding its digital circulation and circulation revenues. The problem is that digital circulation gains will be increasingly less likely to keep pace with declining print circulation and advertising revenues. That the Times is also showing declines in digital advertising revenues will exacerbate the central problem of the Times' continued focus on a traditional print daily newspaper business model. Which is that the digital side is just not big enough to continue to make up the losses from a significantly more expensive print operation.

The NY Times Co., by selling off most of its assets outside its core news operations, has managed to stave off the huge losses experienced by many of its peer brethren, at least for now. But it is likely to have to eventually face the serious question of whether its current business model (and particularly its really high administrative overhead) will sustain operations over the long term.

Source - The New York Times Company Reports 2013 Third-Quarter Results, New York Times Companypress release

This blog is affiliated with a course at the School of Journalism & Electronic Media at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. I'll try to use it to share relevant news and information with the class, and anyone else who's interested.

Thursday, October 31, 2013

Wednesday, October 30, 2013

Another Shift in Viewing Habits

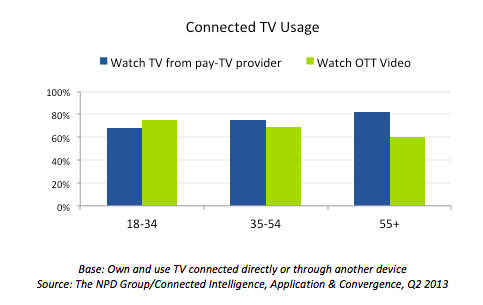

A new study from NPD Connected Intelligence shows that younger TV viewers with "connected TVs" (where the TV or other device connected to the TV can stream online video content) are shifting their viewing patterns towards more nontraditional streaming content. In fact, among 18-34-year-olds in the study, more reported watching OTT (streaming) video on their TVs than reported watching content from multichannel video distributors (cable, DBS, telcom TV).

Source - Three Quarters of 18-34 Year-Olds Use Their Connected TV To Watch OTT Video According to the NPD Group, press release from NPD Group

“The younger consumer has come to expect a broadband experience from any screen they come in contact with, and their TV is no exception,” said John Buffone, director of devices, NPD Connected Intelligence.The big streaming content aggregators (Netflix, Amazon Instant & Prime Video, HuluPlus; in that order) are tops in use for younger viewers, along with YouTube (which now runs second to Netflix). The results come from a survey of 5000 US online adults.

Source - Three Quarters of 18-34 Year-Olds Use Their Connected TV To Watch OTT Video According to the NPD Group, press release from NPD Group

Tuesday, October 29, 2013

Pew: The Demographics behind ABC/Univision's Fusion

Spanish-language broadcaster Univision is working with ABC News on the development of a new cable network to be called Fusion. Fusion will target young Latinos with a mix of news, sports, and entertainment - in English. The folks at Pew Research Center have noted 5 demographic trends among US Hispanics that are behind the move.

Spanish-language broadcaster Univision is working with ABC News on the development of a new cable network to be called Fusion. Fusion will target young Latinos with a mix of news, sports, and entertainment - in English. The folks at Pew Research Center have noted 5 demographic trends among US Hispanics that are behind the move.1. Latinos are increasingly native born (93% of those under 18 were born in the U.S.); Latinos increasingly prefer consuming news in English; 3. 90% of young Latinos get their news, in English, from TV (and increasingly prefer English-language entertainment and music; 4. Even so, using TV for news is declining among young Latinos; 5. A growing share of Hispanics speak only English at home.

Univision, which actually was the most watched network in the US last July among the 18-49 demographic, has seen some of that success fall as the big 4 brought out the Fall PrimeTime big guns. It makes sense for them, looking at their trends and what's happening within their demographic, to expand their expertise with their audience and market by supplementing their Spanish-language channels with English channels targeting their audience segment.

Source - 5 demographic realities behind the creation of Univision/ABC News' "Fusion" channel, Pew Research Center FactTank

Source - 5 demographic realities

Knight on Nonprofit News- Stumbling to viability

The Knight Foundation has just released a study of 18 nonprofit news organizations, looking at what progress has been made in terms of creating a viable economic model. They looked at the news outlets' ability ability to serve their audience by creating unique and relevant content that held value for both readers and communities (social value creation); their ability to convert social value to economic value by growing multiple revenue streams; and whether they were developing a organizational capacity that would allow the continued adaptation and innovation required in an ever-evolving news marketplace.

While perhaps (and understandably) overly optimistic, the report suggests that the most successful nonprofit news organizations share certain traits:

Sources - Finding a Foothold: How NonProfit News Ventures Seek Sustainability, Knight Foundation Report.

While perhaps (and understandably) overly optimistic, the report suggests that the most successful nonprofit news organizations share certain traits:

- Keep questioning assumptions - don't assume you know what your audience wants and needs. Keep track of who your audience is, and what they care about - they're changing, and your organization needs to follow.

- Pursue both niche and need - successful organizations identify underserved niches in their market and target them; while balancing those with more general news and informational needs. "(The) answer to 'who is your audience?' is never 'everyone.'"

- Serve, don't just publish - they realize that their business isn't publishing news and advertising, but developing relationships with their audience that are rich in information and connections.

- Invest beyond content - follows the previous point - to be successful they need to be more than just a source for news stories, and have that a core component of their business plan and operations.

- Measure what matters - and it's not the traditional news metrics of readership. Exploit the data-rich environment of online metrics.

- Move to where your audience is - how people obtain and consume news is changing. The sustainable news organization needs to recognize that, and follow. Don't expect the audience to conform to your preferences.

- Strive for diversity in funding, and build partnerships. News alone won't keep news organizations economically viable over the long term. Look for ways to build relationships with readers and sponsors that can lead to revenue streams into the future. Having multiple revenue streams also helps to keep the organization independent and flexible.

Sources - Finding a Foothold: How NonProfit News Ventures Seek Sustainability, Knight Foundation Report.

Friday, October 25, 2013

Bundling vs. A la Carte - Implications

In previous posts I've explained why bundling can be a good marketing and pricing strategy, particularly for certain types of information goods, and why a la carte strategies can be appropriate for networks with certain characteristics and in markets where access can be easily restricted. I've also made the case that in the early years of cable and multichannel video distribution, bundling was arguably the optimal marketing strategy for system operators, as well as for audiences. Technological advances and the explosive growth in market competition over the last decade or two, on the other hand, have opened the door for the effective use of a la carte marketing of video networks. The remaining core question is whether shifting to a la carte is a good strategy for video distributors, networks, and audiences. I'll try to address that issue in this post.

One of the problems with much of the current discussions of forcing a shift to a la carte marketing is that it's largely based on overly simple, and occasionally inaccurate assumptions.

The one I've already addressed is the argument that bundling forces consumers to pay for channels they don't want. The problem with that argument is that a consumer's decision to purchase a bundle of networks from a multichannel distributor is not based on a network by network consideration of value, but on the simpler issue of whether the consumer feels that the aggregated expected value of the channels he or she does want is greater than the price of the bundle; from that perspective, whether the distributor includes unwanted "costly" channels is irrelevant. ("costly" in the sense that the distributor pays for carriage rights).

A second major assumption (unstated but underlying most discussions) is that the a la carte price for a network would be close to what multichannel distributors pay for carriage rights as part of bundle. The problem with that assumption is that it oversimplifies the market forces at play, and ignores the economic impact of unbundling. For many of the 800+ cable networks available in the U.S., going a la carte is likely to lead to a pricing death spiral.

The problem is that while cable networks in aggregate (i.e. bundled) have been quite successful in attracting audiences (gathering 50-70% of viewing overall (a bit less in primetime), all but a handful of networks attract less than 1% of audience viewing (averaged daily viewing). Of course, some programming draws significantly higher audiences, and demand for networks may be even higher. Still, most cable networks are likely to attract substantially smaller number of subscribers as an a la carte offering than the potential audience obtained as part of a bundle.

For example, the total daypart audiences for ad-supported cable networks in the last quarter showed that only 8 cable networks had overall total day ratings of 1 or higher. Weekly primetime numbers for top networks can be 2-3 times higher, and certain episodes or events (primarily but not exclusively sports) can draw ratings of 10-15. Actual demand for a channel marketed a la carte is likely to be higher than that (as it's aggregating across shows and over time), but is also likely to be highly price-sensitive. Even if a cable network could get a 50% buy-in rate as an a la carte offered at the current bundled carriage rate, that would result in a 50% decline in subscription revenues for the network. (That's one reason pay-tv network subscription prices are in the $15/mo range, while carriage rates for cable networks top out around $5/mo, and most are under a dollar.)

For example, the total daypart audiences for ad-supported cable networks in the last quarter showed that only 8 cable networks had overall total day ratings of 1 or higher. Weekly primetime numbers for top networks can be 2-3 times higher, and certain episodes or events (primarily but not exclusively sports) can draw ratings of 10-15. Actual demand for a channel marketed a la carte is likely to be higher than that (as it's aggregating across shows and over time), but is also likely to be highly price-sensitive. Even if a cable network could get a 50% buy-in rate as an a la carte offered at the current bundled carriage rate, that would result in a 50% decline in subscription revenues for the network. (That's one reason pay-tv network subscription prices are in the $15/mo range, while carriage rates for cable networks top out around $5/mo, and most are under a dollar.)

However, that's not the only impact of shifting to a la carte. Most cable networks are also supported by advertising. While a network would likely keep most of its core viewing as an a la carte offering, it would lose the occasional or drop-in viewers, which would have some negative impact on revenues. More critically, though, is the fact that many national advertisers prefer to buy spots on networks that have a potential reach of 80-90% of the national population. Few cable networks are likely to reach that goal as an a la carte service without significantly discounting subscription prices.

Unbundling cable networks is likely to have significant negative impact on revenues for all but a few channels. Those where losses are small are likely to be channels with established record of high-value content, and a fairly broad audience base. Those channels whose value lies in a narrow niche are likely to find that unbundling will drastically cut their revenues, forcing them to choose between significantly hiking a la carte prices or cutting back on programming costs. Either of those responses put the network on a potential death spiral where demand (and revenues) continue to shrink as networks try to cope through price hikes or cost-cutting in content.

There is one additional implication of shifting from bundling to a la carte. Multichannel video distributors face significant costs in building and maintaining their distribution infrastructure. Those costs need to be recouped through subscription fees. When the subscriptions are for bundles with a large number of, the per-channel distribution costs are fairly low. If consumers shift from a large number of channels to only those they are willing to pay for separately (the goal of a la carte), then those distribution costs would have to be paid for separately, or split among the smaller number of channels subscribed to. In the first instance, that would mean that a multichannel distributor may place a surcharge on access, regardless on how many or which networks are subscribed to. The alternative is to split distribution costs across the channels; meaning networks would have to pay for their distribution, or add distribution costs to their a la carte prices. In either case, that's more negative pressure on revenues and demand.

The upshot is that unbundling will result in significantly lower subscription numbers for most, if not all, cable networks. The lower buy rates will negatively impact both subscription and advertising revenues compared to the current bundling market option. If networks need to maintain current revenue levels, they're likely to have to significantly boost the a la carte pricing, or drastically cost the price (and consumer value of) their content. Either strategy could easily result in a death spiral of declining audiences leading to price-highs and cost-cutting, leading to falling demand and audiences, etc. until the network proves to be no longer economically viable.

The "death spiral" problem is aggravated by the fact that there is a new TV distribution system available. Online video delivery is becoming widely available as broadband Internet access increases. Over 70% of Internet users already watch online videos, and streaming services like Netflix, Hulu+, and Amazon offer access to a vast archive of current and older TV and movie content. The TV consumer faced with the issue of whether to purchase, say, Turner Classic Movies channel is not only thinking about whether that channel is worth purchasing, but the value of TCM vs. AMC vs. USA vs. CNN vs. a Netflix subscription and a plethora of free online content.

Already several million US adults have become "cord-cutters", dropping some or all of their multichannel distribution services in favor of accessing their TV and movie content through online streaming services. If unbundling drives channel prices up and forces consumers to be more rational in their purchasing of subscriptions to access cable networks, this could trigger a move of consumers to online video. That move may well be followed by a move by networks finding a less costly - and more flexible - distribution system that allows more viewer interaction, better usage metrics, and greater capacity for price differentiation.

If unbundling is bad for most cable networks, it's got to be good for consumers, right? After all, a lot of the political push argues that it's in the consumer interest. The reality here is that unbundling is likely to result in consumers paying higher prices for significantly fewer channels. The problem is that bundling acts as a form of cross-subsidization as well as a form of risk aggregation. When value is uncertain, aggregation through bundling spreads that risk - moving the the consumer from "I'm not sure that program/network is worth the price charged" to "It's likely something in the bundle is worth the price." Bundling spreads distribution costs across more networks, reducing per-channel costs. And from the consumer perspective, buying a bundle of channels you're not sure you want while getting those you do essentially subsidizes access to those added channels. Previous efforts to remove subsidies in cable (the 1992 Cable Act) actually increased prices for most cable subscribers, rather than reducing them, as the politicians and interest groups pushing for the Act claimed. In telecommunications, cross-subsidies usually are based on high-demand & high-value services subsidizing low value and low demand services. In this case, it's ESPN subsidizing The History Channel; not the other way around.

Even if the subscription prices of channels don't increase, consumers are likely to reduce the number of channels they will subscribe to. Rather than "bundling forcing consumers to buy channels they don't want," unbundling means that consumers will be able to not buy the channels they don't want. Audience research shows that for most consumers, almost all of their viewing is confined to 5-10 channels. Another factor suggesting reduced channel access can come into play when there are multiple channels or networks in a content niche. If the consumer perceives overlapping value across related niche channels, then the purchase decision is based not on the total value of the additional channel, but the added value that channel is likely to generate above that available in channels already in the a la carte subscription basket. That makes it much less likely that the consumer will purchase complementary channels, or multiple channels within a content niche. At least not without some significant cross-subsidy of channel prices.

So rather than having access to 100s of channels via bundling, it's likely that most Americans would scale back to 5-10 channels, perhaps with occasional video-on-demand purchase of high-value content. Gone would be the opportunity for serendipity and the opportunity to sample and establish value for innovative networks and programs. Thus, unbundling, along with the removal of possible subsidies, is likely to negatively impact general social welfare. In fact, that's the long-established argument for public broadcasting.

To illustrate, a consumer who has a low to moderate interest in news is much more likely to subscribe to a single news source than to subscribe separately to multiple news networks offered a la carte. It's generally given that relying on multiple news and information sources is more valuable than relying on a single source - but a la carte models reduce the likelihood of multiple subscriptions, as the added value of additional news sources decreases as the number of sources goes up. (When content overlaps, the consumer will base a purchase decision on the added value the additional channel will bring, rather than the full value of the channel. Thus further decreasing demand for multiple channels within a niche). I'm sure that most liberals would be upset if Fox News Channel was the only cable news channel subscribed to, just as most conservatives would worry if MSNBC was the only cable news network many people subscribed to.

In addition, the impact of increased costs will hit lower income groups more than others. Lower income groups are likely to cut off a la carte subscriptions once their separate subscriptions reach a point where the channels provide a threshold level of content, particularly if the addition of other channels provide minimal incremental value.

So, a complete unbundling and a shift to a pure a la carte marketing approach is likely to have a significant negative impact on all but the biggest high-value cable networks, and be particularly problematic for networks with content of lessor or unknown value, and those targeting small niche audiences. It's quite likely to increase access costs to consumers (both on a per-channel and aggregate level), and result in their reducing access to networks and content of low or uncertain perceived value. Not only is this a negative consequence for the consumer, but the reduction in access brought by a pure a la carte marketing approach is quite likely to have meaningful negative social impacts as well.

It would hurt multichannel distributors as well, impacting the cost and profitability of their multichannel video services, and accentuating their competitive disadvantage as a TV distribution system vis-a-vis online streaming. The eventual certainty of competitive disadvantage in that field has been recognized by the industry, and is one reason why much of their focus is shifting from multichannel video distribution to becoming a digital telecommunication access point and service provider.

Let me end by saying that a look at the likely impacts of a shift from pure bundling to pure "a la carte" model for multichannel video distribution suggests that there will be serious negative consequences for most groups in the market. But it's not necessary to completely shift from one extreme to another. The growth of video-on-demand (VOD) is demonstrating that a la carte can be a viable option for some networks. The explosion of carriage fee rates for some networks - regional and nation sports networks in particular - suggests that splitting related niche networks and channels into separate mini-bundles, possibly with some a la carte options, would be appropriate and even have a positive impact on consumers and networks, letting the high costs of those channels be born more directly by those that see that value. (And also hopefully bringing bundle prices back down to where multichannel access, and the social values associated with maximal access, are maximized.)

The market and technology is a a point where a la carte marketing of networks and channels is viable, and where it makes sense for some types of channels. The same can be said for the intermediate strategy of offering various mini-bundle mixes of channels, programs, and services. However, there are still a large number of channels, networks, and services where bundling remains the optimal approach, from consumer, network, distributor, and social perspectives. It's pretty clear that rushing into a overly simplistic "bundling is corporate evil so a la carte must be consumer-friendly" assumption is not a reasonable foundation for policy in this area. This is an area where an incremental approach that considers what marketing approach is best within a specific context; where consideration is given to the type of content and its content as well as audience interest, social welfare, and the values inherent in having the content accessible and used. That's the approach most likely to result in positive outcomes.

One of the problems with much of the current discussions of forcing a shift to a la carte marketing is that it's largely based on overly simple, and occasionally inaccurate assumptions.

The one I've already addressed is the argument that bundling forces consumers to pay for channels they don't want. The problem with that argument is that a consumer's decision to purchase a bundle of networks from a multichannel distributor is not based on a network by network consideration of value, but on the simpler issue of whether the consumer feels that the aggregated expected value of the channels he or she does want is greater than the price of the bundle; from that perspective, whether the distributor includes unwanted "costly" channels is irrelevant. ("costly" in the sense that the distributor pays for carriage rights).

A second major assumption (unstated but underlying most discussions) is that the a la carte price for a network would be close to what multichannel distributors pay for carriage rights as part of bundle. The problem with that assumption is that it oversimplifies the market forces at play, and ignores the economic impact of unbundling. For many of the 800+ cable networks available in the U.S., going a la carte is likely to lead to a pricing death spiral.

The problem is that while cable networks in aggregate (i.e. bundled) have been quite successful in attracting audiences (gathering 50-70% of viewing overall (a bit less in primetime), all but a handful of networks attract less than 1% of audience viewing (averaged daily viewing). Of course, some programming draws significantly higher audiences, and demand for networks may be even higher. Still, most cable networks are likely to attract substantially smaller number of subscribers as an a la carte offering than the potential audience obtained as part of a bundle.

For example, the total daypart audiences for ad-supported cable networks in the last quarter showed that only 8 cable networks had overall total day ratings of 1 or higher. Weekly primetime numbers for top networks can be 2-3 times higher, and certain episodes or events (primarily but not exclusively sports) can draw ratings of 10-15. Actual demand for a channel marketed a la carte is likely to be higher than that (as it's aggregating across shows and over time), but is also likely to be highly price-sensitive. Even if a cable network could get a 50% buy-in rate as an a la carte offered at the current bundled carriage rate, that would result in a 50% decline in subscription revenues for the network. (That's one reason pay-tv network subscription prices are in the $15/mo range, while carriage rates for cable networks top out around $5/mo, and most are under a dollar.)

For example, the total daypart audiences for ad-supported cable networks in the last quarter showed that only 8 cable networks had overall total day ratings of 1 or higher. Weekly primetime numbers for top networks can be 2-3 times higher, and certain episodes or events (primarily but not exclusively sports) can draw ratings of 10-15. Actual demand for a channel marketed a la carte is likely to be higher than that (as it's aggregating across shows and over time), but is also likely to be highly price-sensitive. Even if a cable network could get a 50% buy-in rate as an a la carte offered at the current bundled carriage rate, that would result in a 50% decline in subscription revenues for the network. (That's one reason pay-tv network subscription prices are in the $15/mo range, while carriage rates for cable networks top out around $5/mo, and most are under a dollar.)However, that's not the only impact of shifting to a la carte. Most cable networks are also supported by advertising. While a network would likely keep most of its core viewing as an a la carte offering, it would lose the occasional or drop-in viewers, which would have some negative impact on revenues. More critically, though, is the fact that many national advertisers prefer to buy spots on networks that have a potential reach of 80-90% of the national population. Few cable networks are likely to reach that goal as an a la carte service without significantly discounting subscription prices.

Unbundling cable networks is likely to have significant negative impact on revenues for all but a few channels. Those where losses are small are likely to be channels with established record of high-value content, and a fairly broad audience base. Those channels whose value lies in a narrow niche are likely to find that unbundling will drastically cut their revenues, forcing them to choose between significantly hiking a la carte prices or cutting back on programming costs. Either of those responses put the network on a potential death spiral where demand (and revenues) continue to shrink as networks try to cope through price hikes or cost-cutting in content.

There is one additional implication of shifting from bundling to a la carte. Multichannel video distributors face significant costs in building and maintaining their distribution infrastructure. Those costs need to be recouped through subscription fees. When the subscriptions are for bundles with a large number of, the per-channel distribution costs are fairly low. If consumers shift from a large number of channels to only those they are willing to pay for separately (the goal of a la carte), then those distribution costs would have to be paid for separately, or split among the smaller number of channels subscribed to. In the first instance, that would mean that a multichannel distributor may place a surcharge on access, regardless on how many or which networks are subscribed to. The alternative is to split distribution costs across the channels; meaning networks would have to pay for their distribution, or add distribution costs to their a la carte prices. In either case, that's more negative pressure on revenues and demand.

The upshot is that unbundling will result in significantly lower subscription numbers for most, if not all, cable networks. The lower buy rates will negatively impact both subscription and advertising revenues compared to the current bundling market option. If networks need to maintain current revenue levels, they're likely to have to significantly boost the a la carte pricing, or drastically cost the price (and consumer value of) their content. Either strategy could easily result in a death spiral of declining audiences leading to price-highs and cost-cutting, leading to falling demand and audiences, etc. until the network proves to be no longer economically viable.

The "death spiral" problem is aggravated by the fact that there is a new TV distribution system available. Online video delivery is becoming widely available as broadband Internet access increases. Over 70% of Internet users already watch online videos, and streaming services like Netflix, Hulu+, and Amazon offer access to a vast archive of current and older TV and movie content. The TV consumer faced with the issue of whether to purchase, say, Turner Classic Movies channel is not only thinking about whether that channel is worth purchasing, but the value of TCM vs. AMC vs. USA vs. CNN vs. a Netflix subscription and a plethora of free online content.

Already several million US adults have become "cord-cutters", dropping some or all of their multichannel distribution services in favor of accessing their TV and movie content through online streaming services. If unbundling drives channel prices up and forces consumers to be more rational in their purchasing of subscriptions to access cable networks, this could trigger a move of consumers to online video. That move may well be followed by a move by networks finding a less costly - and more flexible - distribution system that allows more viewer interaction, better usage metrics, and greater capacity for price differentiation.

If unbundling is bad for most cable networks, it's got to be good for consumers, right? After all, a lot of the political push argues that it's in the consumer interest. The reality here is that unbundling is likely to result in consumers paying higher prices for significantly fewer channels. The problem is that bundling acts as a form of cross-subsidization as well as a form of risk aggregation. When value is uncertain, aggregation through bundling spreads that risk - moving the the consumer from "I'm not sure that program/network is worth the price charged" to "It's likely something in the bundle is worth the price." Bundling spreads distribution costs across more networks, reducing per-channel costs. And from the consumer perspective, buying a bundle of channels you're not sure you want while getting those you do essentially subsidizes access to those added channels. Previous efforts to remove subsidies in cable (the 1992 Cable Act) actually increased prices for most cable subscribers, rather than reducing them, as the politicians and interest groups pushing for the Act claimed. In telecommunications, cross-subsidies usually are based on high-demand & high-value services subsidizing low value and low demand services. In this case, it's ESPN subsidizing The History Channel; not the other way around.

Even if the subscription prices of channels don't increase, consumers are likely to reduce the number of channels they will subscribe to. Rather than "bundling forcing consumers to buy channels they don't want," unbundling means that consumers will be able to not buy the channels they don't want. Audience research shows that for most consumers, almost all of their viewing is confined to 5-10 channels. Another factor suggesting reduced channel access can come into play when there are multiple channels or networks in a content niche. If the consumer perceives overlapping value across related niche channels, then the purchase decision is based not on the total value of the additional channel, but the added value that channel is likely to generate above that available in channels already in the a la carte subscription basket. That makes it much less likely that the consumer will purchase complementary channels, or multiple channels within a content niche. At least not without some significant cross-subsidy of channel prices.

So rather than having access to 100s of channels via bundling, it's likely that most Americans would scale back to 5-10 channels, perhaps with occasional video-on-demand purchase of high-value content. Gone would be the opportunity for serendipity and the opportunity to sample and establish value for innovative networks and programs. Thus, unbundling, along with the removal of possible subsidies, is likely to negatively impact general social welfare. In fact, that's the long-established argument for public broadcasting.

To illustrate, a consumer who has a low to moderate interest in news is much more likely to subscribe to a single news source than to subscribe separately to multiple news networks offered a la carte. It's generally given that relying on multiple news and information sources is more valuable than relying on a single source - but a la carte models reduce the likelihood of multiple subscriptions, as the added value of additional news sources decreases as the number of sources goes up. (When content overlaps, the consumer will base a purchase decision on the added value the additional channel will bring, rather than the full value of the channel. Thus further decreasing demand for multiple channels within a niche). I'm sure that most liberals would be upset if Fox News Channel was the only cable news channel subscribed to, just as most conservatives would worry if MSNBC was the only cable news network many people subscribed to.

In addition, the impact of increased costs will hit lower income groups more than others. Lower income groups are likely to cut off a la carte subscriptions once their separate subscriptions reach a point where the channels provide a threshold level of content, particularly if the addition of other channels provide minimal incremental value.

So, a complete unbundling and a shift to a pure a la carte marketing approach is likely to have a significant negative impact on all but the biggest high-value cable networks, and be particularly problematic for networks with content of lessor or unknown value, and those targeting small niche audiences. It's quite likely to increase access costs to consumers (both on a per-channel and aggregate level), and result in their reducing access to networks and content of low or uncertain perceived value. Not only is this a negative consequence for the consumer, but the reduction in access brought by a pure a la carte marketing approach is quite likely to have meaningful negative social impacts as well.

It would hurt multichannel distributors as well, impacting the cost and profitability of their multichannel video services, and accentuating their competitive disadvantage as a TV distribution system vis-a-vis online streaming. The eventual certainty of competitive disadvantage in that field has been recognized by the industry, and is one reason why much of their focus is shifting from multichannel video distribution to becoming a digital telecommunication access point and service provider.

Let me end by saying that a look at the likely impacts of a shift from pure bundling to pure "a la carte" model for multichannel video distribution suggests that there will be serious negative consequences for most groups in the market. But it's not necessary to completely shift from one extreme to another. The growth of video-on-demand (VOD) is demonstrating that a la carte can be a viable option for some networks. The explosion of carriage fee rates for some networks - regional and nation sports networks in particular - suggests that splitting related niche networks and channels into separate mini-bundles, possibly with some a la carte options, would be appropriate and even have a positive impact on consumers and networks, letting the high costs of those channels be born more directly by those that see that value. (And also hopefully bringing bundle prices back down to where multichannel access, and the social values associated with maximal access, are maximized.)

The market and technology is a a point where a la carte marketing of networks and channels is viable, and where it makes sense for some types of channels. The same can be said for the intermediate strategy of offering various mini-bundle mixes of channels, programs, and services. However, there are still a large number of channels, networks, and services where bundling remains the optimal approach, from consumer, network, distributor, and social perspectives. It's pretty clear that rushing into a overly simplistic "bundling is corporate evil so a la carte must be consumer-friendly" assumption is not a reasonable foundation for policy in this area. This is an area where an incremental approach that considers what marketing approach is best within a specific context; where consideration is given to the type of content and its content as well as audience interest, social welfare, and the values inherent in having the content accessible and used. That's the approach most likely to result in positive outcomes.

Tuesday, October 22, 2013

Bundling vs. A La Carte in TV Markets - History

Yesterday, I provided some insights from economic theory of information in terms of when bundling can be preferable to "a la carte" marketing of TV channels and networks by multichannel video distributors. The essence was that bundling is actually the optimal strategy for the context of early cable systems and consumers, and has some ancillary social benefits as well. "A la carte" offerings (in economics terms single-use pricing), may work well in other conditions, and the TV marketplace and distribution technology is moving towards those conditions.

Today I want to explore that transition through a historical look at TV market economics, and how that has shifted over time. Tomorrow I'll look at what going to a la carte will mean for today's networks/channels, multichannel distributors, and TV consumers, from a business/economics perspective. To start, let's look at how networks generate revenues from a historical perspective.

In the U.S., the predominant revenue source for stations, networks, and distributors comes from a mix of audience-based sources. For broadcast stations and networks, the primary revenue source comes from advertising, and the amount of revenues an advertisement generates is based on the audience attracted. Historically, broadcast stations who were network affiliates were also paid a fee for carrying network programming, but the amount was, again, based largely on the station's potential audience. Early cable systems were basically redistributors of TV station signals, and the cable system's revenues were tied to the number of subscribers it could attract (i.e. audience size).

When cable networks and channels emerged, they followed one of two basic business models - looking for advertising for revenues, or a subscription-based approach. The subscription model, Pay TV, used a strategy of offering new, and high-value, content not otherwise available to TV viewers in the market, and revenues were directly audience-based (i.e., the number of subscribers). Ad-supported cable networks were miniatures of the broadcast network business model, with revenues based on their ability to attract and retain audiences. These soon discovered that having a focused programming strategy (call it targeting, filling a niche, or branding) gave them a competitive advantage over broadcast networks for the audience segments that valued that type of content more highly. The broadcast networks offered such content occasionally, but the cable network could be a place where viewers could find it all of the time. Targeting also had an advantage in the sense that advertising on niche networks were more valuable for those advertisers who wanted to reach that audience segment. Now there are a few cable networks where the revenues come from sources other than subscription fees or advertising (PBS, C-SPAN, shopping channels, religious networks), but those are still indirectly audience-based in the sense that the funding is based on their programming being able to reach an audience. Bundling allowed cable systems to combine and aggregate the niche audiences by taking advantage of the different mix of high-value networks across audience segments. Bundling increased the value of, and demand for, the bundled mix of networks, allowing cable systems to increase both subscription fees and the number of subscribers.

Revenues are only one side of the business model - the other are the costs of operation. For broadcast stations, networks (broadcast and cable), and cable systems, there are two basic costs - the cost of the programming and content, and the cost of distributing that cost to audiences. The distribution costs for stations is tied to transmission capability, and increasing signal reach is costly. For networks, they need to find a mix of broadcast stations and/or cable systems to distribute their content for them. In the early stages of TV, that meant paying stations or cable systems for carriage, with the larger the potential audience pool the more valuable the distribution channel. Distribution costs for cable systems were substantially different - cable operators face the very high fixed costs of building out the physical distribution network, with very low variable costs. For them, the key was not building raw audience numbers, but in increasing the percentage of homes past that subscribed. That brought the marginal costs per subscriber down to affordable levels.

Turning back to programming costs, there is a general rule of thumb that programming costs correlate with audience popularity (i.e., are more likely to have a high value to some set of consumers). Historically, broadcast TV markets were constrained in terms of both the number of competitors and in their ability to reach viewers in the market - so the only area open for competition within the market was in terms of the programming content offered. Competition tended to drive programming costs up. When cable sought entry, they needed to compete with the existing broadcasters, and the way they could was to offer signals and content that was not easily available otherwise. In the early years, that meant paying to bring new channels, networks, and content into their market. There was the added incentive that bringing in more valued networks and programming content increased the perceived value of the cable subscription bundle and allowed cable systems to increase subscription fees.

Things changed as technology opened markets and the newer networks began to establish their value in the TV marketplace. As TV markets expanded in terms of viewing options, three things happened. First, cable networks largely went niche. They didn't have the resources to compete head-to-head with the broadcast networks for general interest programming and audiences. Going niche let them access lower-cost programming options, yet benefit from the higher advertising value of their audience segment with some advertisers. As multiple niche networks pulled off segments of the general interest audience, viewing of the big broadcast networks dwindled, impacting their ability to generate advertising revenue. The third result is that some of the niche networks developed their brand identities and established their value to the point where having those networks as part of your channel bundle became essential for cable systems. That let those channels switch from having to pay for coverage, to having cable systems pay for their network signals. They had established such a strong expectation of value for their content among a large enough segment of audience, that carriage was mandatory.

The shift in viewing and advertising impacted revenue growth for broadcasters and networks, yet competition drove programming costs ever higher. As a result, everyone started looking for new revenue streams - and carriage fees looked like a viable option. However, as more stations and networks sought to take advantage of this potential revenue stream, those costs were passed on to multichannel video subscribers, increasing the costs of the bundle. In most cases, the added revenues were not used to increase the value of the programming offered (and thus the value of the network to the viewer), but as a replacement for lost advertising revenue. Increasing price without increasing value will inevitably reduce demand for the network, and lower demand results in smaller audiences - particularly in ever-more competitive TV markets.

One factor compounding this is the growth of online video options, many of which combine access to high value content with pricing models well below those available from multichannel video distributors. Another is the fact that eventually the value of carriage fees will ultimately be captured by the owners of the content rather than its distributors (the fee depends on the ability of the copyright owner to limit access rather than any unique aspect of the distribution channel). Finally, as competition in the marketplace advances to the point where most content is available over multiple sources and viewing options, stations, networks, and distributors are finding that having sole access to high-value content is a critical form of competitive advantage. This is the reason why so many networks and distributors are focusing on delivering unique content (not available elsewhere), and why bidding wars are escalating for reliably high-value programming like sports and major cultural events.

From an economic perspective, what this means is that in an increasingly competitive TV marketplace, players are increasingly looking for carriage rights fees as a revenue source, and towards developing a (niche) brand that emphasizes high-value content as a way of increasing demand and value for their outlet. The bidding wars for high-value content drive programming costs higher, and unique content increases the value of the station/network to distributors, allowing stations/networks to try to increase carriage fees collected from distributors, in part to cover the increased programming costs.

Increasing carriage fees mean that the cost of existing bundles is increasing. If the fee increase isn't matched by increased perceived value of the bundle, that will eventually lead to a reduced demand for the bundle. If the multichannel distributor persists in the bundling tactic, eventually price increases will hit a point where the cost of the bundle exceeds the bundle's perceived value by a sufficient number of consumers to trigger a fall in subscriptions. There are increasing indications that we're nearing that point in the U.S.. In particular, there's a growing awareness that the bidding wars for sports rights among a growing number of sports-niche channels is driving big jumps in carriage fees and forcing many multichannel distributors to start thinking about pulling sports networks from the basic bundle, and marketing them as a mix of mini-bundles of sports channels and/or a la carte offerings.

Establishing a reliable brand - in other words establishing a more consistent level of expected value for content - is critical from a consumer demand perspective. As mentioned yesterday, a key advantage of bundling for consumers is that the consumer can mitigate for highly variable and uncertain expected value for content by aggregating across multiple channels and over time. When value is uncertain, it depresses the likelihood of purchase. Aggregating across multiple options means that instead of wondering whether a single program or channel is worth purchasing, the consumer only needs to consider the likelihood that among the bundled options is enough value to justify the purchase. So, if offered a la carte, the consumer's decision shifts to the question of whether they'll receive value in excess of the price they pay for that specific content or channel. This works best when the content is known, high-value, and where such value is relatively consistent across the content offered. That's pretty close to the goals of branding.

Changing technologies are also enabling the other key feature needed for single-use pricing to work - the ability to collect payments and restrict access to the content/network to those purchasing. The growth in pay-per-view and video-on demand offerings from multichannel distributors amply illustrates the technological capacity to offer networks on "a la carte"basis. The growth in niche branding and the success of many channels in building brand value among audience segments similarly demonstrates that, for some networks or channels at least, viewers may have a sufficiently developed idea of the expected value of a network and its programming options to facilitate "a la carte" purchase decisions. The continuing evolution of the TV marketplace looks to be providing a context where single-use pricing models may be viable and practical.

In essence, the transition from broadcast local markets for TV to global, digital, highly competitive marketplace is leading to a situation where bundling is becoming less optimal, and a la carte network marketing is becoming increasingly viable, at least for some networks and channels. While much of the clamor for a switch is politically motivated, the reality of the current TV marketplace is that the ability of multichannel distributors to engage in "a la carte" marketing models for (some) networks is becoming increasingly practical. Additionally, the growth in carriage rights fees is making the idea of a single basic bundle increasingly unaffordable and unsustainable as a marketing approach. The disparity between the growing bundle price and the online video distributors' significantly lower prices is causing many TV viewers to re-evaluate their TV viewing habits and shifting their viewing preferences to lower-cost alternatives. (A phenomenon known as cord-cutting.)

While the early technology and market structure of TV program delivery provided a viable foundation for developing and supporting bundling as a marketing and pricing strategy for cable, the evolution of the TV marketplace (and technologies) is reaching a point where a la carte marketing strategies are becoming practicable. And for some (but by no means all) networks, a la carte marketing structure might be preferable.

But is switching to a full a la carte marketing model a good idea? A lot of that depends on what will be the longer-term impact of a switch, particularly if competition, and programming costs, continue to escalate. I'll address that next.

Today I want to explore that transition through a historical look at TV market economics, and how that has shifted over time. Tomorrow I'll look at what going to a la carte will mean for today's networks/channels, multichannel distributors, and TV consumers, from a business/economics perspective. To start, let's look at how networks generate revenues from a historical perspective.

In the U.S., the predominant revenue source for stations, networks, and distributors comes from a mix of audience-based sources. For broadcast stations and networks, the primary revenue source comes from advertising, and the amount of revenues an advertisement generates is based on the audience attracted. Historically, broadcast stations who were network affiliates were also paid a fee for carrying network programming, but the amount was, again, based largely on the station's potential audience. Early cable systems were basically redistributors of TV station signals, and the cable system's revenues were tied to the number of subscribers it could attract (i.e. audience size).

When cable networks and channels emerged, they followed one of two basic business models - looking for advertising for revenues, or a subscription-based approach. The subscription model, Pay TV, used a strategy of offering new, and high-value, content not otherwise available to TV viewers in the market, and revenues were directly audience-based (i.e., the number of subscribers). Ad-supported cable networks were miniatures of the broadcast network business model, with revenues based on their ability to attract and retain audiences. These soon discovered that having a focused programming strategy (call it targeting, filling a niche, or branding) gave them a competitive advantage over broadcast networks for the audience segments that valued that type of content more highly. The broadcast networks offered such content occasionally, but the cable network could be a place where viewers could find it all of the time. Targeting also had an advantage in the sense that advertising on niche networks were more valuable for those advertisers who wanted to reach that audience segment. Now there are a few cable networks where the revenues come from sources other than subscription fees or advertising (PBS, C-SPAN, shopping channels, religious networks), but those are still indirectly audience-based in the sense that the funding is based on their programming being able to reach an audience. Bundling allowed cable systems to combine and aggregate the niche audiences by taking advantage of the different mix of high-value networks across audience segments. Bundling increased the value of, and demand for, the bundled mix of networks, allowing cable systems to increase both subscription fees and the number of subscribers.

Revenues are only one side of the business model - the other are the costs of operation. For broadcast stations, networks (broadcast and cable), and cable systems, there are two basic costs - the cost of the programming and content, and the cost of distributing that cost to audiences. The distribution costs for stations is tied to transmission capability, and increasing signal reach is costly. For networks, they need to find a mix of broadcast stations and/or cable systems to distribute their content for them. In the early stages of TV, that meant paying stations or cable systems for carriage, with the larger the potential audience pool the more valuable the distribution channel. Distribution costs for cable systems were substantially different - cable operators face the very high fixed costs of building out the physical distribution network, with very low variable costs. For them, the key was not building raw audience numbers, but in increasing the percentage of homes past that subscribed. That brought the marginal costs per subscriber down to affordable levels.

Turning back to programming costs, there is a general rule of thumb that programming costs correlate with audience popularity (i.e., are more likely to have a high value to some set of consumers). Historically, broadcast TV markets were constrained in terms of both the number of competitors and in their ability to reach viewers in the market - so the only area open for competition within the market was in terms of the programming content offered. Competition tended to drive programming costs up. When cable sought entry, they needed to compete with the existing broadcasters, and the way they could was to offer signals and content that was not easily available otherwise. In the early years, that meant paying to bring new channels, networks, and content into their market. There was the added incentive that bringing in more valued networks and programming content increased the perceived value of the cable subscription bundle and allowed cable systems to increase subscription fees.

Things changed as technology opened markets and the newer networks began to establish their value in the TV marketplace. As TV markets expanded in terms of viewing options, three things happened. First, cable networks largely went niche. They didn't have the resources to compete head-to-head with the broadcast networks for general interest programming and audiences. Going niche let them access lower-cost programming options, yet benefit from the higher advertising value of their audience segment with some advertisers. As multiple niche networks pulled off segments of the general interest audience, viewing of the big broadcast networks dwindled, impacting their ability to generate advertising revenue. The third result is that some of the niche networks developed their brand identities and established their value to the point where having those networks as part of your channel bundle became essential for cable systems. That let those channels switch from having to pay for coverage, to having cable systems pay for their network signals. They had established such a strong expectation of value for their content among a large enough segment of audience, that carriage was mandatory.

The shift in viewing and advertising impacted revenue growth for broadcasters and networks, yet competition drove programming costs ever higher. As a result, everyone started looking for new revenue streams - and carriage fees looked like a viable option. However, as more stations and networks sought to take advantage of this potential revenue stream, those costs were passed on to multichannel video subscribers, increasing the costs of the bundle. In most cases, the added revenues were not used to increase the value of the programming offered (and thus the value of the network to the viewer), but as a replacement for lost advertising revenue. Increasing price without increasing value will inevitably reduce demand for the network, and lower demand results in smaller audiences - particularly in ever-more competitive TV markets.

One factor compounding this is the growth of online video options, many of which combine access to high value content with pricing models well below those available from multichannel video distributors. Another is the fact that eventually the value of carriage fees will ultimately be captured by the owners of the content rather than its distributors (the fee depends on the ability of the copyright owner to limit access rather than any unique aspect of the distribution channel). Finally, as competition in the marketplace advances to the point where most content is available over multiple sources and viewing options, stations, networks, and distributors are finding that having sole access to high-value content is a critical form of competitive advantage. This is the reason why so many networks and distributors are focusing on delivering unique content (not available elsewhere), and why bidding wars are escalating for reliably high-value programming like sports and major cultural events.

From an economic perspective, what this means is that in an increasingly competitive TV marketplace, players are increasingly looking for carriage rights fees as a revenue source, and towards developing a (niche) brand that emphasizes high-value content as a way of increasing demand and value for their outlet. The bidding wars for high-value content drive programming costs higher, and unique content increases the value of the station/network to distributors, allowing stations/networks to try to increase carriage fees collected from distributors, in part to cover the increased programming costs.

Increasing carriage fees mean that the cost of existing bundles is increasing. If the fee increase isn't matched by increased perceived value of the bundle, that will eventually lead to a reduced demand for the bundle. If the multichannel distributor persists in the bundling tactic, eventually price increases will hit a point where the cost of the bundle exceeds the bundle's perceived value by a sufficient number of consumers to trigger a fall in subscriptions. There are increasing indications that we're nearing that point in the U.S.. In particular, there's a growing awareness that the bidding wars for sports rights among a growing number of sports-niche channels is driving big jumps in carriage fees and forcing many multichannel distributors to start thinking about pulling sports networks from the basic bundle, and marketing them as a mix of mini-bundles of sports channels and/or a la carte offerings.

Establishing a reliable brand - in other words establishing a more consistent level of expected value for content - is critical from a consumer demand perspective. As mentioned yesterday, a key advantage of bundling for consumers is that the consumer can mitigate for highly variable and uncertain expected value for content by aggregating across multiple channels and over time. When value is uncertain, it depresses the likelihood of purchase. Aggregating across multiple options means that instead of wondering whether a single program or channel is worth purchasing, the consumer only needs to consider the likelihood that among the bundled options is enough value to justify the purchase. So, if offered a la carte, the consumer's decision shifts to the question of whether they'll receive value in excess of the price they pay for that specific content or channel. This works best when the content is known, high-value, and where such value is relatively consistent across the content offered. That's pretty close to the goals of branding.

Changing technologies are also enabling the other key feature needed for single-use pricing to work - the ability to collect payments and restrict access to the content/network to those purchasing. The growth in pay-per-view and video-on demand offerings from multichannel distributors amply illustrates the technological capacity to offer networks on "a la carte"basis. The growth in niche branding and the success of many channels in building brand value among audience segments similarly demonstrates that, for some networks or channels at least, viewers may have a sufficiently developed idea of the expected value of a network and its programming options to facilitate "a la carte" purchase decisions. The continuing evolution of the TV marketplace looks to be providing a context where single-use pricing models may be viable and practical.

In essence, the transition from broadcast local markets for TV to global, digital, highly competitive marketplace is leading to a situation where bundling is becoming less optimal, and a la carte network marketing is becoming increasingly viable, at least for some networks and channels. While much of the clamor for a switch is politically motivated, the reality of the current TV marketplace is that the ability of multichannel distributors to engage in "a la carte" marketing models for (some) networks is becoming increasingly practical. Additionally, the growth in carriage rights fees is making the idea of a single basic bundle increasingly unaffordable and unsustainable as a marketing approach. The disparity between the growing bundle price and the online video distributors' significantly lower prices is causing many TV viewers to re-evaluate their TV viewing habits and shifting their viewing preferences to lower-cost alternatives. (A phenomenon known as cord-cutting.)

While the early technology and market structure of TV program delivery provided a viable foundation for developing and supporting bundling as a marketing and pricing strategy for cable, the evolution of the TV marketplace (and technologies) is reaching a point where a la carte marketing strategies are becoming practicable. And for some (but by no means all) networks, a la carte marketing structure might be preferable.

But is switching to a full a la carte marketing model a good idea? A lot of that depends on what will be the longer-term impact of a switch, particularly if competition, and programming costs, continue to escalate. I'll address that next.

Infographic - Online Video Taking Over

From Getty - a fun look at online video's growth and future in video and infographic.

Part of Getty's purpose is to promote the idea of the video inforgraphics as a better way of presenting data and results visually, instead of having users scroll through a vertically-oriented static infographic.

Some research data highlights:

(edit- forgot to specify online video in header - now fixed.)

Part of Getty's purpose is to promote the idea of the video inforgraphics as a better way of presenting data and results visually, instead of having users scroll through a vertically-oriented static infographic.

Some research data highlights:

- Online video consumption has increased 800% over the last 6 years

- 70% of Internet users have watched online video

- Online video users watch 180 videos a month, on average

- If trends continue, the 18-34 demographic will account for 90% of online video consumption by 2015

- 6.7 million students watch videos of lectures online

- More than 4.6 billion video ads are watched annually

(edit- forgot to specify online video in header - now fixed.)

Monday, October 21, 2013

The Hidden Issues of Bundling vs A la carte marketing - theory

The presumed "debate" over bundling vs a la carte marketing and pricing models for multichannel and online video delivery seems to be heating up over the last year, and looks to become an increasiningly critical question with the rapid increase in rights fees for channels and programs. (For those not up on the jargon, bundling refers to the approach by cable and other multichannel distributors to offer packages of channels at a set price to consumers, while "a la carte" means that channels are offered, and priced, seperately).

The problem is that some of the criticisms of bundling are misleading and problematic, and almost none have taken a look at the downstream implications of a switch to a full "a la carte" model.

Taken in extremis, the critical argument is that bundling is a nefarious (possibly illegal) strategy employed by the giant multichannel operators to force subscribers to pay for channels that they don't want. There's several problems with that position. First, bundling is a well-established marketing and pricing strategy in information economics that is, in some contexts, socially optimal and can maximize consumer welfare. For example, newspapers are bundles of news stories, features, ads, etc., as are magazines, and even TV networks. In a slightly different way, Netflix and Hulu are bundlers, offering access to a range of content offerings for a fixed monthly fee. On the other end of the continuum is what the media industry is calling "a la carte", or in economic terms, single use pricing models. (There is actually a wide continuum of options between a single bundle and single unit pricing models, but I'll focus on the extreme cases).

The field of information economics has long indicated that bundling is a valid pricing/marketing strategy, and in fact can be socially optimal under certain conditions - when the bundled offerings have uncertain or highly variable value to consumers, and when the consumers cannot be easily differentiated. This is important, because when the audience can be easily differentiated, then the supplier can charge some more than others for the same set of goods. When it can't, then the social surplus (the difference between what a consumer gets in value above the price paid) goes to the consumer. When the supplier can differentiate access, then they get to capture some or all of that consumer surplus through differential pricing.

There are two other important social advantages with bundling - it allows consumers to sample and establish values for content (which gives unknown, low-interest, and/or low-value content the potential to establish a market), and it allows the benefit of serendipity (finding important or valuable content unexpectedly).

As for the argument of forcing people to pay for channels they don't want, that's hogwash. When content is bundled, consumers base their purchase decision on their individual aggregated expectation of value. That is, consumers look at the likely content offerings, and aggregate their expected values for the content they want. If their aggregated value is higher than the price, they buy; if not, they are free to not buy the bundle. The advantage of bundling is that it can accommodate a wide range of value choices and ways to hit that aggregate value target - for one consumer, access to sports channels and content may create that aggregated value, to another, it may be a combination of access to news, science, and history channels; to another, it could be PBS, Nickelodeon, Cartoon Network and Disney. In all of these cases, the consumers base their purchase decision on getting the content they want, and everything else just comes along with the bundle. No one is forcing anyone to "pay for" channels they don't want. Bundling can also be looked at as the high-value channels cross-subsidizing low-demand channels.

In the early days of cable and multichannel distributors, the content was pretty clearly the kinds of new channels and content that makes bundling the best strategy, for distributors as well as consumers. It was also a good strategy for the various cable networks/channels - enough so that in the early days most paid cable operators to get into that basic bundle. Getting into the bundle was particularly important for networks/channels that used advertising as a primary revenue source - being included in the basic bundle gave them access to the largest potential audience, while letting those in the audience sample their programming without added cost and letting networks build the demonstrable audience base that provided value to advertisers. And the payments from channels to cable operators helped to subsidize the price of the bundle, again helping them grow the market. Another advantage of bundling is that, in maximizing potential audience, it spread distribution fixed costs (which tend to be quit high among multichannel distributors) over larger numbers of subscribers and reducing the per-subscriber cost of distribution.

However, the cable/multichannel market has changed, increasingly moving away from the type of content that bundling is the optimal strategy for. Most networks have now established their expected value to consumers. In addition, technology now permits greater ability to control which channels are accessible by which subscribers, allowing more differential marketing options. Technology has also expanded video delivery options, some of which face significantly lower costs. The most significant shift, though, is in the rights fees paid for content. Rather than subsidizing the price of the bundle, the shift to the multichannel distributor paying rights fees, and the rapid rise in the amounts of those fees, are pushing the price of the bundle to a level where consumers are taking a second look at their willingness to pay. Particularly when the Internet is providing a range of content alternatives at substantially lower prices.

The industry and market may be approaching the point where offering a single bundle, or a few tiers with dozens of networks/channels, may not be the best marketing strategy for either the multichannel distributor or the TV consumer. But are we at a point where a pure "a la carte" strategy is optimal for either the distributor or consumer of TV networks?

The industry and market may be approaching the point where offering a single bundle, or a few tiers with dozens of networks/channels, may not be the best marketing strategy for either the multichannel distributor or the TV consumer. But are we at a point where a pure "a la carte" strategy is optimal for either the distributor or consumer of TV networks?

The economics of information suggests that single-unit pricing (pure "a la carte") works best when there is a group of consumers that has established a reliable, and relatively high, set of expected value for the specific set of content - and where distribution of that content can be restricted to only those consumers. The technological capabilities for differentiation are increasingly there. Further, some channels/networks that have done a good job of establishing a relatively high set of expected values for their content through branding (ESPN, Nickelodeon, Disney, etc.), at least for some portions of the audience. For those, going a la carte, or minibundling (a small group of networks with similar content or brands), may be marketing/pricing strategies worth exploring. However, for other channels, going a la carte alone may not be a viable option.

For example, during the recent CBS/TimeWarner rights fee squabble, TimeWarner offered to let CBS market its network "a la carte" at whatever price it wanted. An offer that CBS rejected out of hand, suggesting that it felt that going solo might not be a great business strategy at this time.

The CBS reaction points to another issue, which I'll address more fully in a separate post; that most networks/channels get funding from multiple sources, some of which are tied to audience size. The problem with going "a la carte" is that consumers would then apply their purchasing logic to the individual sets of channel(s) being offered separately. That is, TV consumers will pick which channels they'd be willing to pay the market price for, and which they wouldn't - and viewing habits suggest there are few channels that wouldn't face huge drops in audience if they went a la carte, particularly if the price was more than minimal. With the potential of significant declines in audience-based revenue streams, that could create a pricing death spiral for many channels.

Let me close this piece by referring back to the social side-benefits of bundling. With bundling, the consumer retains most of the consumer surplus value, instead of it going to the distributor (with minibundling) or the network (with a la carte). Bundling maximizes consumer access to the broad range of content choices; giving new content and channels the opportunity to establish value with consumers, and allowing for viewers to benefit from serendipity or to access the occasional content a channel might present. Finally, bundling maximizes potential audience for channels, allowing them to benefit from audience-based revenue sources, and lower per-subscriber distribution costs.

Bundling can be a reasonable and consumer-friendly pricing strategy in theory, at least in some circumstances. Still, circumstances can change, and there are also other economic issues to consider.

The problem is that some of the criticisms of bundling are misleading and problematic, and almost none have taken a look at the downstream implications of a switch to a full "a la carte" model.

Taken in extremis, the critical argument is that bundling is a nefarious (possibly illegal) strategy employed by the giant multichannel operators to force subscribers to pay for channels that they don't want. There's several problems with that position. First, bundling is a well-established marketing and pricing strategy in information economics that is, in some contexts, socially optimal and can maximize consumer welfare. For example, newspapers are bundles of news stories, features, ads, etc., as are magazines, and even TV networks. In a slightly different way, Netflix and Hulu are bundlers, offering access to a range of content offerings for a fixed monthly fee. On the other end of the continuum is what the media industry is calling "a la carte", or in economic terms, single use pricing models. (There is actually a wide continuum of options between a single bundle and single unit pricing models, but I'll focus on the extreme cases).